Too often we define the Medtech sector by the number of dollars raised, IPOs helped or companies sold. But the focus neglects the very foundation of the sector: the people. Join the Medtech Talk Podcast each month to hear from entrepreneurs, investors and executives who spend their days developing the tools that make sick people well and health care more efficient.

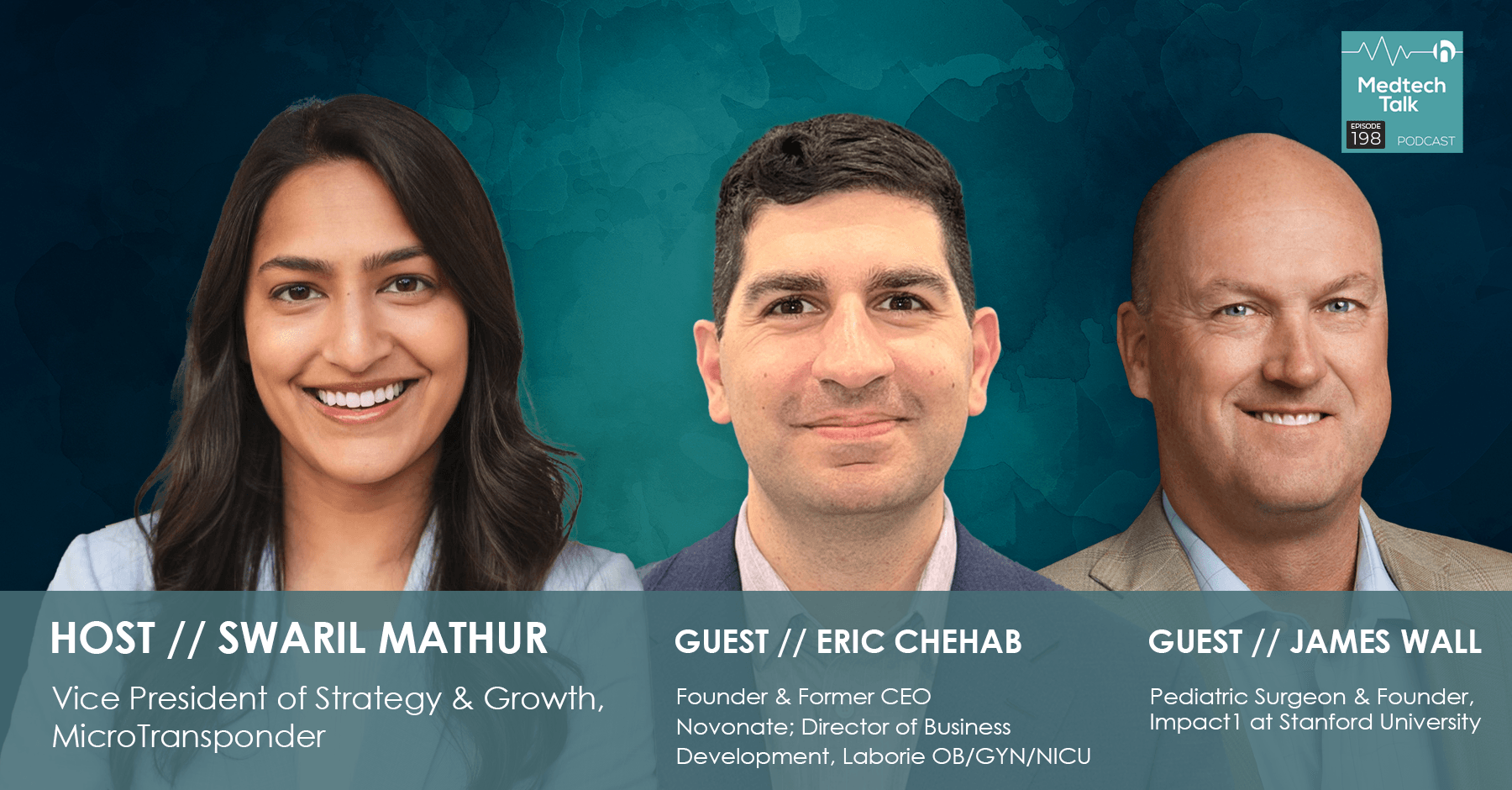

Niche markets and small populations don’t get the attention they need for medtech and healthcare. Medtech Talk host Swaril Mathur speaks with Eric Chehab, founder and former CEO of Novonate and director of business development of Laborie OB/GYN/NICU, and James Wall, pediatric surgeon and founder of Impact1 at Stanford University, about how they’re bringing medtech innovation to small patient populations. They delve into their experiences of founding their own niche market companies and the lessons learned, including how they navigated commercialization and acquisition processes, convinced the right investors, determined capital efficiency, and more. They also share their thoughts on investors who think niche solutions for niche markets are uninteresting.

GUEST BIOs

Eric Chehab, Founder and Former CEO of Novonate; Director of Business Development of Laborie OB/GYN/NICU

Eric Chehab is a biomedical engineer who received his BS from UC San Diego, and MS and PhD from Stanford University, where he studied musculoskeletal biomechanics and knee osteoarthritis. In 2017, he founded Novonate, a medical device company that developed high-impact product for patients in the neonatal intensive care unit. Novonate developed and launched LifeBubble, a revolutionary product for umbilical catheter securement and protection. Eric was Novonate’s CEO until 2023, when the company was acquired by Laborie Medical Technologies. Eric is currently the Director of Business Development for Laborie's OB/GYN/NICU division.

James Wall, Pediatric Surgeon & Founder of Impact1 at Stanford University

James Wall is a Professor of Pediatric Surgery at Stanford University who specializes in minimally-invasive approaches to children’s surgery. He is a physician entrepreneur who has developed multiple health technologies from idea to commercialization. James is the former Director of the Stanford Biodesign Innovation Fellowship. His passion for building sustainable businesses that address the needs of underserved patients led him to found the Impact1 program at Stanford focused on accelerating health technology development for pediatric, maternal, and fetal patients. The programs that he led at Stanford have been responsible for the development of health technologies that benefit patients globally. James joined Intuitive Surgical in 2023 where he is focused on Advanced Product Development.

HOST BIO

Swaril Mathur, Vice President of Strategy & Growth, MicroTransponder

Swaril Mathur is a strategic growth leader with deep expertise in building and scaling transformative medical technologies through early-stage innovation, M&A, and go-to-market execution. Most recently, as Vice President of Business Development at Axonics, she led M&A and strategic initiatives, including the company’s $3.7B acquisition by Boston Scientific. Prior to joining Axonics, Swaril drove early-stage innovation at Edwards Lifesciences as a member of the Advanced Technology group, and at Stanford University as a Biodesign Innovation Fellow. In these roles, she partnered with engineers and physicians to identify and address unmet clinical needs in cardiology and otolaryngology. She remains actively involved with Stanford Biodesign, currently co-teaching its Global Faculty Training program, which equips international leaders to support needs-driven healthcare innovation in their home countries.

Swaril began her career at Boston Consulting Group, supporting strategic transformations and business integrations for leading healthcare clients. She holds an M.S. in Bioengineering from Stanford University and a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering from the University of California, Irvine.

TRANSCRIPT

Swaril Mathur:Welcome to MedTech Talk. This is your host, swarrel Mather. The focus of today's episode is innovating for niche populations. Niche clinical problems are often overlooked, not because the needs aren't real, but because the markets aren't big, and on today's episode we'll explore what it takes to be successful in that arena and what success even looks like. I am so excited to have this conversation with two guests who have deep experience in this topic Dr James Wall and Dr Eric Chahab.

Swaril Mathur:Dr James Wall is a physician innovator. He's a pediatric surgeon at Stanford Children's Health. He was formerly the director of the Stanford Biodesign Innovation Fellowship. He is the vice president and associate Medical Officer for the DaVinci Multiport Robot at Intuitive Surgical, and he's the founder of Impact One, which is an initiative at Stanford specifically focused on pediatric and maternal health innovation. Eric Chahab earned his PhD in bioengineering at Stanford University, where he founded Novanate, a neonatal medical device startup that we will talk a lot more about shortly. He was the CEO of Novanate until its sale to Labry in 2023, where he is now the director of business development, and I'll note, James and Eric have worked together. James was an advisor to Novanate, which is how these two incredible people know each other. So, James and Eric, welcome to the podcast.

Eric Chehab:Thanks so much, Swaril. Really excited to be here with you and excited to take a strip down memory lane.

James Wall:Yeah, thanks for having us Swaril.

Swaril Mathur:Great, all right. So, James, Eric, you know, the reality is that medtech innovation is expensive, and commercialization even more so, so it can be hard to justify building and scaling a business that is going after a small TAM. And it's hard, yes, but I think the two of you have worked really hard to prove that it's not impossible, and so I would love to tell some of the stories of what you've worked on and what techniques and methods you've learned for how to innovate successfully for small populations. So, James, let's start with your story. You're a pediatric surgeon. Tell us how you started to tune into the need for innovation tailored to pediatric populations.

James Wall:Sure, tailored to pediatric populations. Sure, so you know, my story goes back to really starting as a biomedical engineer in undergrad and, you know, learning about medical devices and wanting to, you know, think about ways to get involved in innovating, inventing and ultimately making an impact for patients. I went on to med school and then I chose pediatric surgery as my specialty and, you know, fast forward a few years. I found the biodesign program and learned about innovation, and that's when really, this dichotomy hit me that you know, as a pediatric surgeon, I realized that things that I was using in the operating room on a regular basis really were not designed for kids and for their unique diseases. We were really adapting. So every day of the operating room it was adapting instruments often made for the adult population, very large instruments for very small patients, and that really didn't hit me.

James Wall:Until I went to biodesign, I began to learn what you don't learn in medical school about innovating. You have to understand market size, market access, all the barriers to entry of a market, whether they be regulatory or payment, et cetera. And when you learn that process of innovation, you realize that it really is difficult to innovate for small populations in terms of absolute numbers of patients. And so I began to understand this dichotomy that there's all these great medical devices being developed you see a lot of them for adult cardiology, diabetes, et cetera and why I wasn't seeing any being developed for me.

James Wall:And having that understanding, I began to think huh, you know, could we do things differently within a realistic framework that understands that we're in a capital market system? We do generally have to take investment in order to get devices to the market. What are some strategies that we could potentially come up with? And kind of step number one was to see if we could do it ourselves. And when Eric and I met at Stanford over a decade ago that's kind of where part of the journey began was saying you know, the idea that Eric and his team had from a graduate class in biodesign I found compelling. I thought the market opportunity was small and challenging, but they had really defined such a great value prop that I thought it was worth a shot. And I'll let him talk about that and then go and maybe go back to how that kind of formulated one of my first strategies that really focuses on value for PEDS.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, absolutely Absolutely. Now, thanks for that introduction, and it's funny that you bring up kind of the biodesign process, because even within that right, there's this process of choosing the most compelling needs, and often part of that is filtering based on market size right, and you and I have talked in the past about the fact that there's a very intentional choice you make about what you're going to filter by, and, while many companies and many innovators will choose to filter by market size and choose the things that have the biggest dollars, you could also filter by impact, and it sounds like that's something that has influenced a lot of the things you've worked on. And also Eric. So you know, eric, I think we absolutely want to tell the Novanate story because it's such a good example of the lived journey of actually innovating for a niche population. So can you tell us kind of how that originated, what that came out of and why you decided to pursue it and what Novonate was?

Eric Chehab:Yeah. So I took the graduate biodesign course and we were assigned a general problem statement of central line associated bloodstream infections or CLABSIs being a problem and to start research in that space. So we started, you know, we started listing out all the different types of central lines that different patients in the world get. You know, everything from hemodialysis to sort of chemotherapy and everything in between, and we started kind of listing them out, looking at their infection rates and their complication rates. And eventually we sort of started looking at the pediatric population, listing out all the different types of central lines in the pediatric population, and pretty quickly realized that the complication rates and infection rates are just a little bit higher in pediatrics. Sure, the incidence is lower because the kind of overall number of patients is less, but the rates were higher, which meant, you know, it was kind of more clinically compelling value proposition. So then we started segmenting out the different types of pediatric central lines and we eventually learned of something called an umbilical cord catheter, quite literally looked around the room, including the med students, and asked them what an umbilical cord catheter was. They did not know, so we typed it into Google Images and we kind of saw this crazy picture of this central line that comes out of the belly button, that is held at an upright angle, going through this desiccating piece of tissue that is kind of suspended in midair with a piece of tape that is kind of built as a bridge from the abdomen, and that looked wild and we couldn't believe that that was how Stanford University would do it. So we went and found a neonatologist or the med students did, rather and the neonatologist pretty much said, yep, that is exactly how we do it here at Stanford. And so we knew we were onto something, you know, clinically meaningful.

Eric Chehab:We recognized that it had a smaller market opportunity compared to some of the other needs that we had uncovered, but it just felt very clinically compelling and seemed like a simple solution could be viable. Very clinically compelling and seemed like a simple solution could be viable. And of course, if you're just filtering based on TAM, it would not bubble to the top. But we couldn't get out of our heads that it would be a pretty simple solution, a pretty low cost of development in face of that kind of smaller TAM, and we felt like we might have had a shot to make the economics work. So we got some good feedback.

Eric Chehab:We kind of presented at the end of the course. We wanted to keep it going. This team sort of tried. It fizzled off, honestly. But then a couple of years later one of my colleagues it wasn't even me revived the project and came to me and said hey, let's get this going again. Let's see if there's something we can do. Let's bring together a new team. He's the one who found James. Originally we needed a PI for a grant. I think we typed in like pediatrics biodesign.

Swaril Mathur:And what was the thinking at that point? Now you're years past this. You're trying to revive this project. What was going on in your head in terms of picturing? What was this going to look like? Did you have big dollar signs in mind? What were you hoping for?

Eric Chehab:Yeah, no great question. I mean at first it was just can we develop a clinically meaningful technology that can have an impact on patients? That's kind of how it started. Frankly, when we brought James in, I think James was the one who looked us in the eyes and said if we're going to do this, we need to do this as if we're going to start a company and that's the way it'll actually get to patients.

Eric Chehab:And I think James actually put like a lot of legitimacy to that academic endeavor where people were kind of all working on it part time, you know, for a couple of years or so.

Eric Chehab:And, you know, even though we sort of incubated within the university and, you know, developed it slowly but steadily I remember we were meeting every Tuesday morning, James, at 8 or 9 am for a couple of years and making slow and steady progress. At that point we recognized that if we were really going to get this going to patients, we needed to have kind of a whole startup company thing in mind and we sort of designed a company, not just the product but design a company around this product, so that we could hit the ground running if and when we spun out of the university. You know, I remember explicitly James and I and others had a conversation like I think. James said no one's retiring off this technology or off this company, and we knew that to be true, but we knew that we had to have it make at least some potential economic sense to get it to the finish line, yep, yep.

Swaril Mathur:So tell us what the first few years I know this was a long journey, right, but tell us kind of what. The first couple of years were working on this product and, specifically, as you were ideating what the concept or what the solution was going to be, and then testing, prototyping, building that solution, what were the things that you all had to do? Very differently because this was a small population compared to how you might have done things if the population was 100 times that size.

Eric Chehab:Yeah, I'll start really quickly.

Eric Chehab:I mean, when we were still a Stanford-based team for about the two years before we spun out at the university and became Novenate, it was great because we didn't have much overhead, we weren't paying anyone salaries.

Eric Chehab:We got like a $90,000 grant, which took us a very long way because we just, you know, 100% of it essentially went to R&D and so we were able to take that time to really develop prototypes, get creative, take it to clinicians you know, physicians but also a lot of NICU nurses get their feedback, you know, design different testing rigs and we were able just to be scrappy because we did not have the pressures of like burn rates or investors at the time. So that was kind of the ideal environment for the product that would eventually become a life bubble. So when I was in the university, I think, yeah, we were able to kind of do that. And then once we became Novate, it was really just staying capital efficient and, you know, brought investor dollars in, recognizing that we couldn't over-raise, and just finding people that could do a lot of different things and, yeah, just getting really efficient with product development in early stages.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, and James, maybe a question for you. As you've I mean you advised Novanate, but you've also advised several other companies that have tried to innovate for niche populations, I hear the need to be you know capital efficient in the development process. What does that actually mean in terms of the decisions you're making, for example, when you're brainstorming and just in the early stages of trying to figure out what is our solution even going to be? Is that the stage at which are you applying filters around? We're only going to look at solution concepts that would be a 510k, not a PMA, or we're only going to look at technologies that would be quick and cheap to develop and manufacture, as compared to things like active implantables? What are the guardrails that allowed you to even be capital efficient, maybe at some of these other companies as well?

James Wall:Yeah, and I think what's important about me advising these companies is I actually started with companies going after larger markets. Right, I did the BioDesign fellowship. I founded Insight Medical Technologies, which could be a whole different podcast in terms of learning, but going after a much larger epidural anesthesia market, getting it through regulatory, garnering investment, hiring a CEO, all that sort of stuff. I also had the great opportunity to work at Kleiner Perkins as an intern and interact with, you know, just an unbelievable group at the time, including Brooke Byers and Beth Seidenberg and others who were, you know, actively investing in biopharma and med tech and really looking for home runs. That was their model right and so, and I got the chance to sit on some boards as a relatively young up and comer in the industry and that just opened my eyes to, you know, how some companies approached medtech development around going after big targets, going really fast, spending a lot of money on IP protection, et cetera, et cetera Kind of what we were taught to do if you're going to do medtech right, and and a lot of what influenced some of the ways that we filtered things in biodesign, where we often filtered large opportunities, and I think for me, that experience allowed me to formulate early on what I thought were two key strategies for innovating in a niche market. And the first was what Eric said, which is focus on value. Right, there has to be a huge value prop. And I think the way I summed, you know, I actually heard one of the more famous Silicon Valley investors say one time, or said to me personally, you know, I always go for the biggest possible bullseye because I can afford to miss right, just in terms of TAM, like just in a strategy, and I was like, okay, well, that one's, you know, not possible. So what you know? So now we've got to think the opposite. We've got to think, okay, we're actually aiming for a really tiny bullseye, so we got to be laser focused, that we're going to deliver value. So kind of strategy number one. And what Eric and Carl and Lauren and some of the other people who are involved in Novonate early and I talked about was let's be sure, right, let's be sure these infections are more common, that there's there's real opportunity to improve patient outcomes and improve economics for hospitals and really a product that could do that can become a sustainable business. So that was sort of lesson number one, strategy number one Novena proved it. But that was kind of learned from working on adult opportunities, where maybe big was good enough without a clear view of the value, and so that was number one.

James Wall:And then capital efficient. Yeah, how does that work? It's trade-offs right. To be capital efficient simply said, you have to make trade-offs right. You simply can't spend money as fast as you possibly can if you're going to really try and be capital efficient. The point of being capital efficient, of course, is that there's only a certain number of potential exit opportunities for a niche market. Right, there's only so many acquirers, potentially so many companies in the space. So the less you are in, the lower your absolute valuation. You can still potentially return money to investors, and so we really focused on that. But the trade-offs for me are time right, how fast you can get to market, and that's one that's probably okay to make right.

James Wall:There's not a lot of competition in these spaces.

James Wall:So you know, burning money to go fast is probably not as important. And that's where you can do things like. You know, wait for six months for a grant to come in. You know, do a lot of work in the university. Keep the overhead low. You know, use partial time. We used a program at Stanford early on, before this was ever thought to be a company, just a project. We had some students volunteering time and that was great. And then the other. You can trade off things like IP too. Right, you don't have to have the world's most robust IP portfolio across the globe. That can cost hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars If you're in a relatively small niche space where competitors are not going to rush in to go after your huge margins and opportunity, because that's not who you are. So those are a couple, but there's other things you can imagine along the way that you can trade off. But really time and the kind of spending we did on adult stuff was not necessary in my opinion, and that's how we played it out with Novanade.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, yeah. A question that comes to mind for me is around clinical evidence, right, because that's an area where a lot of spend is generated for medical technology innovation. So how have you thought or how have you seen kind of these companies tackle that question of how to run efficient, lean clinical studies, which sounds like an oxymoron?

James Wall:Yeah, well, I'll speak to that one and I'll let Eric add on. But I think, Eric, you'll probably agree with that was the biggest bet we made on Novanate. I would say the biggest bet we made. You know, we had developed the product on grant funding within Stanford to the point where it was like ready to be manufactured. We then decided, okay, we're going to spin it out, we're going to try and make this a startup. We had customers ready, so there was very little commercial risk. There was very little technical risk. We had filed some IP, but the one thing we didn't have was clinical evidence and we sort of we polled, we talked to the customers.

James Wall:There's only so much you can do, right, you know, obviously everybody wants to show a difference in the most meaningful outcome, which in this case would have been CLABSI, and CLABSIs were give or take three to 5% at that time in the neonate population. And you know, showing a difference of 50% would have been meaningful. 50% reduction would have led to significant cost savings, significant improvement in morbidity, mortality. But it would have taken a lot of patients in each arm of a study if you were going to do a large randomized control study, and that would have probably doubled the cost of development. So we said is there a surrogate outcome that we think is good enough, at least for the early stage of innovators, early adopters, that we can get the product to market, show that there's kind of unit economics that work, that it can get to profitability and sustainability. It's not going to be a billion-dollar company but it's got to have those fundamentals in place.

James Wall:And that's the bet we made. We said we think we can do that and so we used something we looked at line migration, which is pretty common. Lines come out. The studies are all over the place, but in the 20 to up to 60% of the time you can have line migration and that leads to having to remove the line and replace it and a lot of people associate that migration and replacement with an opportunity for an infection to happen. So, short of proving the actual infection decrease, we thought that proving line migration, which was doable in, you know, something like 50 patients as opposed to several hundred, was really the way to go. And that was the bet we made that we could get to market, we could at least get to early adopters through that and then, once we got to early adopters, we could potentially use real world evidence or other strategies that are capital efficient to prove our ultimate goal, which is to reduce infections.

Eric Chehab:Yeah, and just a little more detail on like how we made that bet and what's that risk looked like. So the product was actually 510k exempt as class one device. So we took it to market and commercialized it in air quotes before we put it on a single patient. You know, rather than apply for an IDE and sort of do a pre-commercial like pivotal trial or something like that, also dealing with sort of a neonatal population, and felt like it was the right thing to subject ourselves to the FDA requirements before putting it on patient and not asking for any shortcuts. So we did that. So we, you know, registered it with FDA and then put it on patients. And as we were doing some customer discovery, and I was spending tons of time speaking to NICU nursing leaders and neonatologists and started shifting our messaging more around umbilical venous catheter migration, recognizing that that was resonating a lot more quickly, because there will be some NICUs who say, oh yeah, you know, clabsi rates are 3%, but not in our NICU, you know, it hasn't happened in two years.

Eric Chehab:These obliquely venous catheter migration rates are like 30, 40% and it clicked a little more quickly and I was speaking, as I was speaking with a bunch of physicians, there was one in particular. It just resonated with him and he told me almost verbatim that it's like his number one pet peeve in the NICU.

Eric Chehab:And so we structured something where we essentially gave him some money to do his own independent clinical study for this PI driven grant. You know we had no control over it really took a long time to complete but but that was, you know, very capital efficient and he was just very clinically interested in improving that already. So finding the right partners right helped out a lot.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, yeah. And so it brings me back to something that James had mentioned earlier, which is, you know, since your bullseye is smaller, you've got to really nail it. There's no space to miss. And you know, to that point, it sounds like you were getting great direct feedback from the key stakeholders, so that when you made these trade-offs, you were making the right trade-offs right. I think that's an area where a lot of startups get into hot water. I mean, even the big, well-funded startups have to make trade-offs, but it's just the question of how do you know which ones to make and how do you validate that you're making the right ones. So that's really helpful. And while we're talking about the notion of kind of being capital efficient, I want to talk specifically about funding strategies. So, throughout kind of the lifetime of Novonate, can you tell us how this venture was funded? What worked, what didn't work? Like did you even approach traditional MedTech venture investors? Did they even take your calls? What was this process?

Eric Chehab:Yeah. So before we spun out Novinate but in the sort of six months before we did, knew that that was going to happen started applying to all the pitch competitions, applying to grants and put ourselves in position to meet investors. We applied to present at UCSF's Rosenman Institute and gave a presentation to them and met a couple of people who were starting a venture capital fund, which was medical technology venture partners you know, partnership with the Rosamond Institute and this just clicked with them and I remember we gave the presentation. It was very quick. It was in a room with a bunch of people. We didn't even know who everyone was and someone who might have been James or maybe Ross said well, if you guys know anyone who'd like to invest in this, let us know. Quite literally, as we're walking out the door, someone raised their hand and said well, I would.

Eric Chehab:And we had no clue who that guy was and he didn't even have a business card because they hadn't even closed their first fund yet. But we found our way back to him a couple of weeks later. Long story short, and that was where I do and ended up being on our board and kind of a primary VC behind Novanate. We applied for grants. Sbirs were a big source of funding eventually, the Pediatric Device Consortia as well, and a few other kind of grant-based things here and there, and then, yeah, primarily MedTech Venture Partners and then a series of angel investors along the way, funded the company.

Swaril Mathur:Great, and what was the value proposition to them?

Eric Chehab:Yeah, I mean we kind of framed it realistically. You know what the TAM was, but what the development cost would be and the fact that we had de-risked so many things in the years prior, and so I think the investors who invested in it whether it was VCs or angels kind of viewed it as a low risk opportunity, not something that's gonna generate like a very high return. But for the ones that are looking for what some investors call the base hits, in addition to their home run potentials, this could be a base hit opportunity.

Eric Chehab:So I think, that there were certainly some that said just too small market opportunity. I don't invest in pediatrics, but for those who are kind of looking to diversify their risk, you know in their portfolio this resonated.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, yeah, James, I'm curious. You know from again from the other companies that you've advised are there other common funding strategies or what is your typical advice when companies are trying to figure out what funding sources they should try to tap?

James Wall:Yeah, so in terms of giving advice to the early stage innovators, which is kind of really what we built Impact One to do we'll probably talk about that later but we really advise them to. You know, think about the most efficient use of funds early and where they can get non-dilutive funds right, and everyone kind of talks about non-dilutive funds, but there's a lot of ways to do it. Typically, universities are the best place to get non-dilutive funds. Stanford is particularly good in terms of having a number of different programs. You know we were involved in everything from StartX to culture funding, et cetera, et cetera. So these are all generally funds that the university gets from either foundations and or philanthropy and or programs that have been established, and that money is distributed to innovation style projects, and so that's kind of one great area to do it if you're within a university, and these vary across universities, but you get the gist of it. There's also federal dollars. So SBIR, sttr a lot of people know about those programs. Those are small business, innovation or tech transfer awards and those are really focused on projects that probably couldn't be developed by a company because they're too risky in terms of spending. You know P&L dollars on R&D, and so they are focused on external entities, but early stage med techs can take advantage of those and I think a lot of people in our community are much more familiar with them these days.

James Wall:And then the last is sort of what I call you know, philanthropy to sustainability right, so there's pure philanthropy, which you know. Philanthropy to sustainability right. So there's pure philanthropy which you know usually expects impact but maybe not return or doesn't think of it in terms of a business right, just donating to you know some particular cause of. You know typhoid fever, you know whatever that you know that they want to sort of like. You know fund, you know solutions to, and the money gets spent and impact is created.

James Wall:When I think about philanthropy to sustainability, it's about really focusing on the kind of person who gives money, who probably has a business background maybe, who's been very lucky in venture or whatnot tech, particularly in our area of the world, in the Bay Area, who really understands that you can build a business on unit economics that may not be worth $10 billion but they can be sustainable, can grow and can kind of work in perpetuity. But to get that started you need a little boost right, and that boost can be non-dilutive philanthropic dollars as opposed to venture dollars. That you know, venture is great, but they have LPs who expect returns and they have a thesis that they have to hold. And if that doesn't fit with a niche development opportunity, then I think philanthropy is a real opportunity. But it really needs to be framed and I'm not asking for a donation here. I'm asking for a kickstart to a sustainable business.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, and when you say sustainable business, do you mean kind of long-term profitable business, meaning you guys expected even at that point that the unit economics were going to work out such that you know you're you're making more than you're shelling out yeah, I mean, I think it's that simple right, like if, at some point, you're making more than you're spending, you have your future in your hands, right.

James Wall:You may or may not be able to reinvest in additional projects. You may not to be able to grow as fast as you want, but you are in control. You can continue to deliver the product to the patients and grow at a rate that you know, within the bounds of the capital you have on hand. Before you get to that point, you're relying on ongoing investment, and so I think you're also, once you get to that point, or you have visibility to, you know, kind of break even, cashflow positive, either of those. Then you're at a point where you become much more attractive for acquisition and that was one of the key unlocks of Novonate is we got to that point where we proved that the market, you know, was willing to pay um at a price, that that for which we could be profitable, we could move towards being, you know, cashflow positive and ultimately could potentially even break even, and that's when I think the business really was much more attractive to potential acquirers.

Swaril Mathur:So you know you've mentioned, of course, the goldmine is to get to profitability, right, but I want to talk about how that's possible, because the big thing in my mind is commercialization. Right, we've talked a lot about how do you stay capital efficient through product development and clinical studies, but now the big question mark is okay, you have this product that's useful for a very small population. How are you going to commercialize it in a way that's sustainable and makes financial sense? So, both with Novonate and with other companies that you've worked on, James, how did you think about that? What was the go-to-market strategy?

James Wall:Yeah, I'll talk about the strategy and then I'll let maybe Eric talk about how he implemented it. But the strategy we had, or the insight, maybe not even to the level of a strategy yet, but the insight was that we were really going after a focus group of customers, right, when you think about most adult med tech, you think about 8,000 plus hospitals if hospitals are your customer or hundreds of thousands of potential physicians around the country, you know, when you're talking about the NICU, you're talking about very consolidated care in hospitals. You know a couple hundred hospitals around the country that are really high level NICUs and a very small number of providers compared to adult specialties. And so sort of strategy number one was focus on the biggest NICUs, which are really consolidated, and you don't need an enormous sales team to do that. And in fact I'll hand it over to not only our CEO but our early head of commercialization and sales, Eric, to talk about how he implemented that strategy, because we weren't going to hire a sales team, right. So, Eric, take it away.

Eric Chehab:Yeah, that's right. I mean we would have loved to have a big enough budget to hire direct sales force, even a few people, to cover the country and kind of fly around, but we really couldn't afford it. So we had to think a little bit outside the box and nothing too unusual, but really an independent sales force that we are paying, based on commission, where sure there is new risk there and managing kind of a third party is challenging, but at least where they're not sort of adding to the burn rate, we're not paying fixed salaries if they're underperforming and that of course takes a hit on our product margin and that of course takes a hit on our product margin. But you can start to think very clearly. You know how to scale that up and how many accounts or how many units per month, per year you would need to become cash flow positive. You know, probably stripping away a lot of the other things at that point in time.

Eric Chehab:But we had a pretty clear plan in place and we had fumbled around our commercialization strategy a bit. We had tried a few different things, but we did find a group who we were working with and started ramping things up with to kind of deploy this nationally under that model where we're basically just paying them a royalty, if you will. And that was the strategy. And then you know myself, and then hopefully we had raised a little more money, someone to manage that team, provide them with like all the marketing tools kind of a sales strategy, if you will, obviously staying on top of it and make sure that they're being sufficiently effective. And that was the plan and we started. We started down that road and then strategic discussions with Labry picked up at that time and eventually kind of became we got acquired then by Labry.

Announced :Are you enjoying the conversation? We'd love to hear from you. Please subscribe to the podcast and give us a rating. It helps other people find and join the conversation. If you've got speaker or topic ideas, we'd love to hear those too. You can send them in a podcast review.

Swaril Mathur:You know it makes sense that you would have to go through kind of independent distributors in order to commercialize this, because that's obviously a lot more capital, efficient and more flexible than building your own sales force. But again back to the notion of trade-offs. Right, there's trade-offs of doing that. You then don't have direct control over this outside entity and you're competing for their time and attention and effort with other things that are in their bag which, again, you might not even have visibility into. So what did you learn in the process of trying to figure out who are the right distribution partners to work with and what does the structure need to look like? What are some of the key learnings that you had there?

Eric Chehab:Yeah, it's a great question and probably one of the most difficult things that I did at Novenaid. And you know I really wanted to make sure we found the right partners. In the early days we, you know, worked with a few reps through an intermediary, with the incentives weren't like totally aligned and we really didn't control enough through that phase and those reps were quite unsuccessful at getting the product into different hospitals and just realizing that the incentives weren't sufficiently aligned. Then we started looking at different specialty distributor groups, you know ones that were familiar with neonatology or selling pediatric devices, and that was really interesting to us and we were sort of marching down that road.

Eric Chehab:The challenge with that is we would have kind of had to piece together the whole US, you know, finding a group on the West Coast, another on the East Coast, another like in Texas, and there probably would have been seven or eight groups that that that you know were needed to kind of make up the coverage of the whole country and and I was intimidating to manage for for me or really anyone else on our team trying to be lean, really anyone else on our team trying to be lean so then we found a group that was actually not very familiar with the neonatal space but very familiar with the central line and central line securement space and a single company that covered the whole US and only were selling kind of four other products.

Eric Chehab:So we would be the fifth. So it made sense that we could kind of get their attention and we were sufficiently optimistic that we could teach them how to sell into the NICU, provide them the tools to be successful in the space, and that was kind of the initial pilot partnership that we struck. We never worked with the whole team prior to acquisition, but for about a year we worked with a subset of their group and sort of scaled up. But the lesson learned was really just making sure that the incentives are as aligned as possible, that you're providing with the tools necessary to be successful and you know, even though it's not the same company to treat it as close of a partnership as possible.

Swaril Mathur:Mm-hmm, Mm-hmm, Absolutely. Now. The Novanate story is a success because Novanate was eventually acquired by Laboree, as we alluded to, and I would love to kind of talk more about how that happened. I mean, I think the preconceived notion that most of us have is that big medtech companies chase billion-dollar TAMs, right. So why did this acquisition happen? How did this fit for Laboree and what did your conversations with them look like?

Eric Chehab:Yeah, a bit of a long story but in short, I think when we started having a line of sight on what profitability would look like and what James was talking about, we had a clear plan of what it would take to get there. Our board, our investors, encouraged us to start strategic discussions. So I remember, you know, I was tasked with providing a strategic overview of every company that could potentially acquire us, who we knew in those companies or who we needed to know in those companies. We have like a couple hour meeting. I went through each of them one by one, what the strategic rationale could be and we sort of assigned tasks. I mean James included.

Eric Chehab:You know, I think James took a couple of companies to find someone at a certain company to connect with and that kind of kicked things off and that was to be clear, probably two years before acquisition. But it started this process of establishing relationships, quarterly or so check-ins by me with the people that we connected with at each of those companies, giving them the updates, seeing if they wanted to discuss things. On that company list was a company called Clinical Innovations who we connected with sort of on and off over the years. Clinical Innovations eventually got acquired by Labry and so the OBGYN NICU division of Labry was sort of legacy Clinical Innovations and during just one of those check-ins things kind of resonated. Obviously internally there was some strategic shift on their end and asked us to kind of give a renewed set of presentations to a new leadership team and things kind of picked up.

Eric Chehab:So you know, it wasn't necessarily an explicit decision of, hey, we need to sell this company right now, but a slow and steady process of establishing relationships. And then you know, eventually the stars aligned.

Swaril Mathur:And it sounds like a lot of how deals get done, which is it's slow, and then it's fast, right, it's a slow process of reaching out to folks, building relationships, and then there comes a tipping point where someone's ready to act and it moves fast. I'm curious, in some of those early conversations you were having with a broad list of strategics, what was some of the feedback you were getting? What were some of the things they were excited about? What were some of the things they were hesitant about?

Eric Chehab:Yeah, great question. So as a generalization I would say, you know, the clinical need resonated and for the strategics that were pretty familiar with this space they got it very quickly and it made logical sense. You know, for some strategics there's a question of whether they wanted to invest further in the neonatal space right, if they weren't a NICU-focused company maybe they had one product to NICU in their bag whether there was an explicit desire to grow into that space and invest further in that space. Clinical nations and library independently identified the NICU as an opportunity of growth. They're primarily a labor and delivery-focused company and sort of viewed the NICU as an opportunity of growth. They're primarily a labor and delivery-focused company and viewed the NICU as an adjacent space to grow into.

Eric Chehab:It was great that we didn't have to convince them of that opportunity. Strategic alignment, I guess, is the phrase that admittedly I probably use these days a little more than I should, but conversations about whether this was aligned with where they wanted to take the business. But I frankly did not have to have too many discussions or conversations to convince them of the clinical need and of the potential clinical value, probably because we spent all that time in the early phase.

Swaril Mathur:Mm. Hmm, yeah, and that's back to James. Yeah, and that's back to James's earlier point that you know one of the keys if you're going to innovate in this space is to focus on value proposition, and that holds true across every stakeholder. So you had spent some time building relationships with different strategics. You started to get a good sense of where there was good strategic alignment. Was there any debate about you know, whether it really was the right time to sell the company or what the valuation should be about?

James Wall:whether it really was the right time to sell the company or what the valuation should be. Yeah, so, as a member of the board a very small board, myself, one investor and Eric we really were a working board for a lot of this journey, and Eric alluded to a process that we initiated that I think is really important. When you're in the pediatric and maternal space, there's not a lot of potential acquirers, so I think a real intentional effort to build relationships with them early and connect with them often is important. You know, as many of our mentors say, companies are bought, not sold, and I think that's right. The strategic has to have some idea of the space and interest, but keeping those relationships warm are important and when the time's right, I think you can accelerate things, and so was great to have that process going before we were out of cash or in a tight spot or really looking to sell, if you will.

James Wall:And actually, early on, there was one offer made from a smaller company.

James Wall:It was not the most generous offer and so, but it was an offer and as a board of a company that knew its biggest potential barrier might be exit in terms of the ability to scale right To join a larger company with more resources, with more of a sales force.

James Wall:It was an opportunity to do that at a price that was pretty, pretty hard to wrap our heads around and we actually said no to it, which was potentially the craziest thing that's ever been done in pediatric innovation is to say no to an acquisition offer. That being said, it gave us the discipline we did the modeling. It was a hard 72 hours for Eric, more so than the rest of us, but we were all sweating it. But it gave us conviction right, it gave us conviction. We've been in the market, we know what our margins are, we think we can hold to them. The product's becoming sticky, we think we have a strategy for selling it, we think that can be scaled and if that is all true which we had conviction in then the value of the company is higher and we should keep going. We should work towards cashflow positive to have our you know, kind of have our future in our hands and then find a potential partner who sees that value and ultimately, labry was that partner and things really worked out for everybody.

Swaril Mathur:Wow, that's pretty incredible.

Swaril Mathur:I mean, the idea of being in such a niche space and still deciding from a limited set of potential buyers to turn something down must have been more hand-wringing than you're letting on, but obviously, ultimately you made the right decision and there was a great outcome for the company and for the product and for all the patients that are benefiting from it now.

Swaril Mathur:So we've talked a lot about the Novanate story in particular and I know this is one of many innovations that you've worked on, James that is related to niche populations your passion particularly aligning with pediatric and maternal health and I want to hear just a little bit more about Impact One, which is this program that you started at Stanford with a specific mission to support and accelerate innovation for niche populations. Can you tell us briefly what is Impact One, what is its objective and what are some of the key lessons, key learnings, that you are trying to instill in innovation for niche populations? Can you tell us briefly what is Impact One, what is its objective and what are some of the key lessons, key learnings, that you are trying to instill in?

James Wall:these innovators that you are advising? Yeah, so Impact One came out of that early dichotomy of my career where I really saw that there was a lack of innovation, a lack of medical devices being developed for the unique diseases and needs of children and also maternal patients, as I have part of my practice in fetal medicine and when you look at it objectively, children are 25% of the population and, as I like to say, they're 100% of the future. So I thought they deserved more. I thought that we could build an initiative that could help promote. And how do we do that? So, first, what's your mission statement? It's to impact lives from day one, both day one of life, day one of pregnancy and to do it globally. And so the way we do that in Impact One, or the initiatives that we've built, are education and really the Impact One initiative, to be clear, lives within the biodesign program at Stanford, so really aligned with the biodesign mission of impacting lives globally, with really much more of a focus on pediatric and maternal patients, who've been underserved by our industry and others. And so really, it begins with education, you know. And the way we do that is that we have a forum. This is a funny story, is that we started this forum probably a decade ago and the idea was we would have innovators who had ideas in pediatric and maternal come to the forum and present their project or idea, whatever stage they're at, and that we would provide advice, guidance, some coaching, based on the fact that some of us had done startups and understood the biodesign process, teach them to define the need, um, etc. And I was really worried, for, you know, after about six months we would run out of projects, right like there would just be none left because there were so few people working on this. And you know, fast forward a decade. We've expanded it globally, but we now have two forums a month, three companies per forum, six companies a month presenting. We have 60 plus companies who apply for seed grants through our pitch competitions annually for both pediatric and maternal, and we've just had some pretty incredible impact.

James Wall:So it started with education. Next, I was able to raise some funding, initially through collaboration with UCSF and the Pediatric Device Consortium, grants from the FDA. We were able to get funding to support the program, to bring in some fellows to start giving out seed funding to companies. We then were able to enhance that funding with philanthropic donors who have given to the program, allowing us to really expand the reach globally, and that money really allows us to do the next step, which is enabling innovators right, really doing translation.

James Wall:And so translation's about not just that early education and coaching but giving them resources through, you know, directed grants to get an FDA regulatory consultant to do a prototype, et cetera, whatever they need early on in their journey to help de-risk the project we can fund with directed grants. And then we have these seed grant competitions that give away up to $100,000 per company per year to support them in the early stages. And then, finally, we do some policy work, which could be a whole kind of podcast on its own, so I won't go into it in too much detail, but really thinking about the ways that you know policymakers think about PEDS and make sure really at a fundamental level they're just included in the conversation and thought about when policy decisions are made. So those are kind of the three cornerstones of the program.

Swaril Mathur:Wow, yeah, so really just a breeding ground for kind of innovations that are going after niche markets, particularly related to pediatric and maternal health.

James Wall:Exactly. And then the final part that we've done in more recent years is try and create an ecosystem outside of Stanford and the current mechanism for that something I learned from Brooke Byers, who really built a lot of the biopharma industry on a conference where it wasn't just companies he invested in, but really all companies that were groundbreaking in the space came together. We've started a pediatric and maternal CEO conference and, again, 10 years ago I didn't imagine there'd be more than five or 10 CEOs of pediatric and maternal companies, but we now have 50 plus who attend on an annual basis. Last year we were in New York City, this year we're going to be in Austin, and the conference is really building a community of leaders in this space who I hope will not just be one-time CEOs but will be multiple-time CEOs, will mentor the next generation and really build a community that has conviction, belief in the space and the know-how to get it done.

Swaril Mathur:Yeah, wow, that's pretty incredible, and even hearing this is changing some of my preconceived notions about how much action there is in this space. Right, it's funny when you know. Even hearing this is changing some of my preconceived notions about how much action there is in this space. Right, it's funny when you said we're doing a CEO conference, in my head I immediately started picturing a very small conference room in some hotel. You know some hotel's first floor. But it's eye-opening and really encouraging to just hear how much action there is actually out there once there are platforms for it to be supported and for these people to connect with each other.

Eric Chehab:Yeah, and I'll just add briefly someone who's a part of that community. It's tangible the difference that it makes and, being at that most recent conference, this world of pediatric med tech startups is small but it's mighty and it's almost abnormally supportive of itself. And you know there is not a lot of competition happening in the pediatric device world and and there is common challenges that occur specifically around fundraising and go to market strategies and it's just an ecosystem where where the different CEOs, the different founders are so eager to help each other out and so supportive, and so having these kind of structure of organizations that bring these people together, provide an ecosystem to allow them to kind of collaborate and help, you know really makes a difference.

Swaril Mathur:That was a great overview of Impact One. Yeah, that's really encouraging to hear. Eric and James, can you give us a sense, kind of, since Impact One was founded, what's kind of the scope and scale of the impact that the program has had?

James Wall:And so, since 2019, we've supported over 210 projects across 19 countries and six continents. We're still shooting for Antarctica. We haven't gotten there yet. The projects that we've supported, through both coaching directed funds as well as seed funding, have now reached 90,000 plus patients globally. Those companies have raised about $240 million, they've created over 400 jobs and we've had four companies exit, so we're really proud of the accomplishments. Again, it's not all about company creation, but companies as vehicles to deliver impactful medical technologies to pediatric and maternal patients. So stay tuned there's a lot more to come.

Swaril Mathur:Great so, james and Eric, it's been so rewarding to hear kind of the stories of the companies that you have guided and built that have successfully innovated for niche populations. I know there are a lot of folks out there who work in medtech, either on the investor side or in business development, and these big strategics who have preconceived notions about what makes an attractive market. So what's the one thing that you would say to an investor or a big strategic who just thinks that niche solutions for niche markets are not interesting?

Eric Chehab:So I would encourage anyone who is intimidated by a niche market or a niche TAM to keep in mind the clinical impact that a product can make. You can still have a very big clinical impact in a smaller market opportunity. To some extent, that's why we all work in this medical technology world is to impact patients, to improve lives, to save lives in some cases and to just sort of do good for the world, and I think it's important to keep that in your heart and consider that as you make investments or strategic moves.

James Wall:Yeah, I think. To add to that, my first piece of advice to investors would be don't use the term niche market. It's a market, right? I've heard that term used in the past around women's health, and that was bonkers. Women are half the population. That's a huge market. So my advice is don't think niche, think it's a market. If you stick to your fundamentals of assessing TAM SAM SOM, you stick to your fundamentals of understanding the unit economics of the product, understanding the value proposition that's being created, then you really can assess whether there's an opportunity there. If you're worried about things like regulatory risk and things that are unknown to you because you haven't worked in the space before, come talk to people like us. Right, it's been done. There's now models for it. So my advice is stick to fundamentals and, if there's any uncertainty, learn from those who have done it. There are real challenges, but there's also significant opportunity in the space.

Swaril Mathur:Absolutely Well said. Thank you both for coming on the podcast today and sharing your stories. I think this conversation was a really powerful reminder that small markets can drive huge impact and shouldn't be overlooked, and we just have to be willing to rethink how we innovate, how we fund, how we scale these journeys, and so this was a really, really powerful story. Thank you both for being here and MedTech Talk listeners. We'll see you next time.

James Wall:Thanks, Swaril.